Super Habla

The Brief

“How Might We help cleft palate patients in Ecuador recover their speech after surgery, given that there are only 2 cleft-trained speech therapists in the country?”

Interviewing a family at their home in JipiJapa, Ecuador. They used to travel four hours to get to a speech therapist, but had to stop after a second child.

Interviewing a family at their home in JipiJapa, Ecuador. They used to travel four hours to get to a speech therapist, but had to stop after a second child.

In 2016, we took on this challenge as a part of Stanford d.school’s Design for Extreme Affordability class. After working closely with Fundacion Rostros Felices, an organization providing surgery and some speech care to patients in Ecuador, we identified three challenges for speech therapy in this context:

Insights

We interviewed dozens of parents, children, and caregivers (plastic surgeons, speech therapists, social workers), and realized that speech therapy for cleft patients needed to solve three primary issues.

Engagement // Speech therapy is incredibly boring and repetitive for kids. Parents have to cajole their kids:

“Pablo, pleeeeeeease…. If you do this therapy, we will go get ice cream. Do you want ice cream? Please… there is just a little bit left.”

Access. // Even dedicated and motivated parents have access problems.

“[the cleft-trained speech therapist] lives four hours away. I took my child to her three times, but when I had my second child, it was too difficult to keep going.”*

Effectiveness. // Local speech therapists do exist, but aren’t trained.

“I have tried three speech therapists locally who have worked with my child. He hasn’t made progress. With this latest one, at least he co-operates, but he doesn’t speak any better.”

Prototype I: Booklet of speech therapy activities

Access was a huge problem (only 2 speech therapists in Ecuador), so we wanted to solve that problem first. The main design problem was: how might we get in-home speech therapy to occur?

We knew that without the kids’ engagement, therapy at home wouldn’t continue very long. And ineffective strategies would not help the kid improve. So we picked the most engaging of the speech therapy practices used by traditional therapists, and packaged them into a booklet, along with lots of information for the parent to get up to speed on how specific sounds were produced.

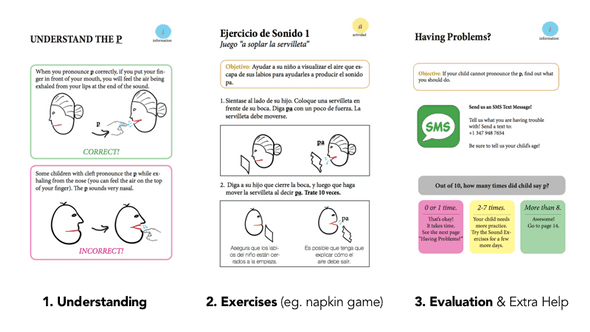

Sample pages from the booklet for the p sound. The booklets contained speech therapy activities, but also information to train moms to deliver therapy at home.

Sample pages from the booklet for the p sound. The booklets contained speech therapy activities, but also information to train moms to deliver therapy at home.

Early tests had seemed promising: one mom told us that her kid who didn’t do therapy at home finally started to play the napkin game included in the book. Kids were enjoying some other activities (including a roulette) as well. However, after interviewing parents, we realized that while some of the activities were fun, the book format echoed homework. Visual information was helpful to the parents, but they ignored most of the sections that required reading, including the bits on evaluation. As one mom put it, “its not that we can’t read—we can, we just don’t like to.” Learning: The activities we provided in the book were fun and useful. A book, however, had connotations of homework, and most text-heavy pages were not used by parents.

Prototype II: Board game w/ just the activities

We then decided to create a behavioral mechanism that would ensure daily usage of the most popular and useful part of the book: the activities. We created even more activities, and packaged them up in a boardgame-inspired layout, complete with bold and bright colors for the kids.

Our boardgames. We took what was fun from the book (the activities), and created packaging to connote “this is a game, not therapy”.

Our boardgames. We took what was fun from the book (the activities), and created packaging to connote “this is a game, not therapy”.

User testing with this game gave us much more positive results. The kids loved the new game and its activities, and the colorful materials, and the game-like look of the setup. But we had a lot of activities, some of which still involved reading, and some activities were definitely more fun than others. The amount of imaginative play that kids participated in also varied between the US and Ecuador, and some game features that were a hit in the US (like a “SuperHero” card) totally fell flat in Ecuador.

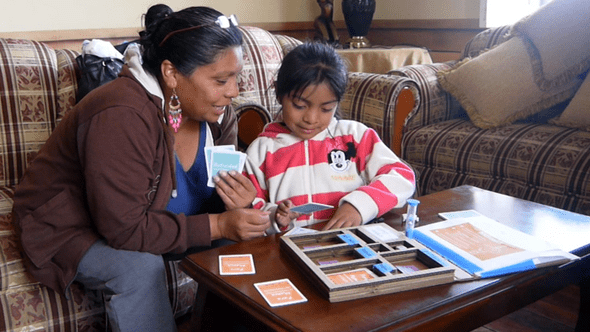

Mom and patient testing out our board game.

Mom and patient testing out our board game.

Another thing we noticed was that despite starting quite well, the dynamic between kid and parent often worsened after a while. For most of the activities, there was a “success” criterion, whose judge was the parent. However, this created a dynamic where instead of being in a support role, the parent became an evaluator of the kid. The kid’s challenge for that day was literally meeting the parent’s standards for an activity. Driven by the desire for their kids to achieve better speech, parents would often want their kids to practice even when the kids no longer found the activity fun or engaging.

Learning: The fact that the mom is an evaluator creates a negative relationship between kid and parent.

Prototype III: Card game: hiding vitamins in cupcakes

In our third design cycle, we wanted to create the right interpersonal dynamic between child and parent. In order to take the evaluation role away from mom, we decided to “hide the vitamins in the cupcakes,” and make the repetitive speech therapy invisible. We created game mechanisms where just playing the game needed repitition, so the kids didn’t even notice the rules.

The smiles last a lot longer in initial tests with our latest prototype.

The smiles last a lot longer in initial tests with our latest prototype.

After a great response to this game, we are now working on full-scale manufacturing of the game and a hand-off to SmileTrain, a global non-profit that provides tens of thousands cleft-related surgeries a year.

Top Learnings from the Project:

- Design is about testing and iteration. This project helped me understand, deeply, that the most powerful part of the design thinking process is actually iteration. The end of the “empathy” phase of the process creates a good hunch about the solution space, but it’s a hunch nevertheless. The real test comes when you put designs in front of users.

- Ethnographic research happens through immersion, not interviews. Particularly when it comes to cross-cultural research, a lot of the learnings come from being attuned to taking in everything—you have to do a lot more than interviews and intercepts. Keeping a constantly curious mind, talking to partners incessantly, and being hyper-aware of the interactions around you can open up new avenues of investigation that you didn’t know were possible.

He has designed products, developed software, and created collaborative efforts across five continents, and currently lives in the SF Bay Area.